Ad for Sue’s return

Dunlap and Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

10 Jul 1779, Sat, Page 4

Newspapers.com

Sue or Susan

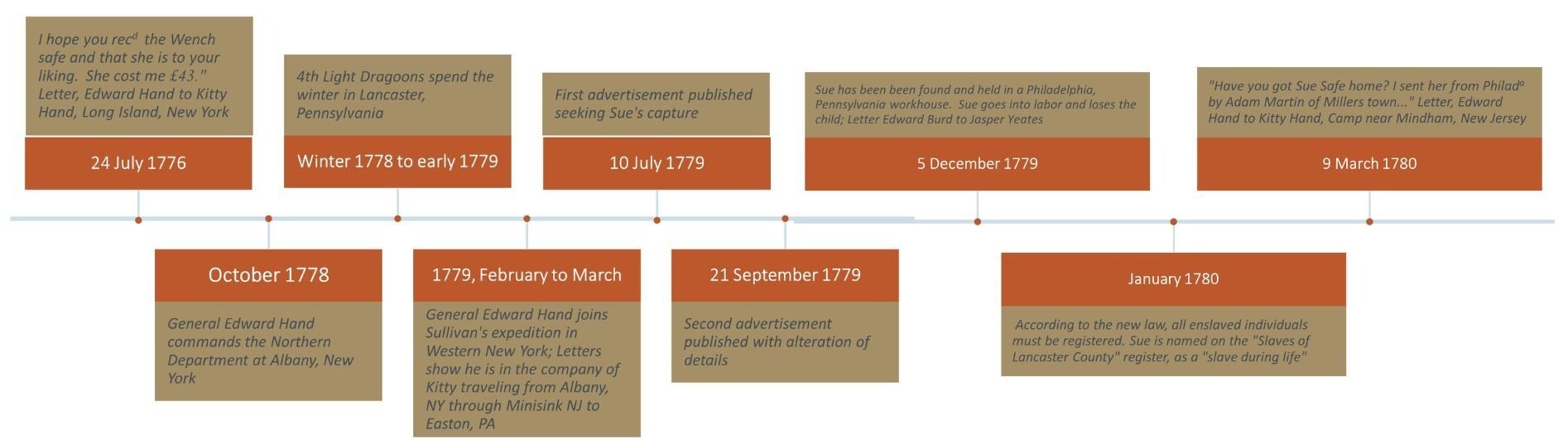

On July 24, 1776, Lieutenant Colonial Edward Hand wrote from his camp in Long Island to his wife Kitty in Lancaster to inquire about the arrival of an enslaved woman he had purchased for her. Subsequent records indicate that this woman’s name was Sue.

“I hope you rec’d the Wench and she is to your liking. She cost me £43….”

Letter, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

Three years later, on July 10, 1779, while Hand was still away at war, he placed an advertisement in a Philadelphia newspaper seeking Sue’s apprehension after she escaped from his home in Lancaster. Hand placed the ad several times over the next few months altering the information one time until the final ad appeared on September 21st. Hand offered a 100 dollar reward for Sue’s capture and detention. In the language typical of the period, he described her physical characteristics and demeanor, and first estimated her age at 30 years but amended it to 25 or 26 years in subsequent publication. Hand also noted that Sue was “big with child”.

Based upon information conveyed to Hand, he suggested that Sue may have been traveling toward the location of the 4th Regiment of Light Dragoons in Philadelphia with a white woman who had ties to the unit. The Dragoons had encamped in Lancaster several months before Sue’s self emancipation affording her the opportunity to interact with its members and camp followers. Alternatively, Hand suggested that she may endeavor to return to Long Island, her previous home.

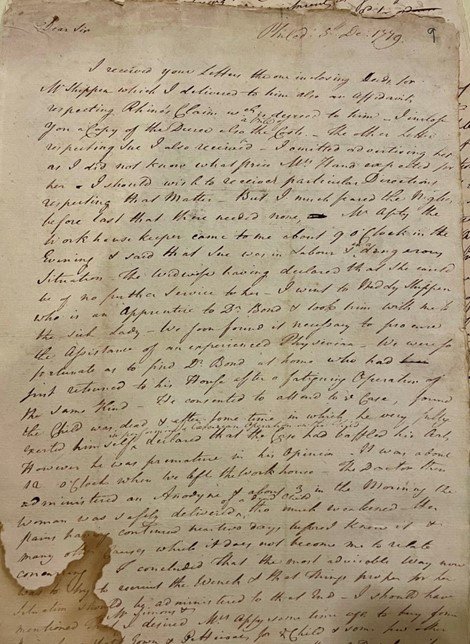

Sue’s freedom was short-lived. A letter dated December 5th, 1779, from Edward Burd in Philadelphia to Jasper Yeates in Lancaster described a dire situation involving the enslaved woman bound by the Hand family. Sue had been recaptured and was detained in the Philadelphia Workhouse, a building within the High Street Gaol complex where convicted criminals were imprisoned.

With Edward Hand engaged in the war, Jasper Yeates, uncle of Kitty Hand, often assisted his niece with matters of business. In this instance Yeates had obtained the help of Edward Burd, his brother-in law, to advertise the sale of Sue after her recapture on behalf of the Hand family. Burd wrote to Yeates to communicate that he had not done so in part because Sue was close to death from complications related to childbirth.

A day before the date of the letter, Edward Burd was notified by the workhouse administrator that Sue was in labor and had been attended to by a mid-wife. The mid-wife had declared that after many hours of unproductive labor, it was beyond her capability to deliver Sue’s child. Burd described in his letter his subsequent efforts to engage additional assistance and the extraordinary measures used to deliver Sue of a deceased infant. Burd then listed all of the expenses he incurred in his efforts to assist the Hand family with Sue expressing that these costs did not exceed the ”value” of the slave in his estimation and implied that reimbursement was expected.

The archaic language used in this document and the traumatic events described may be offensive and disturbing for some readers. Please exercise caution before viewing. To view a transcript of the letter from Burd to Yeates click here.

Sue’s horrific experience in childbirth within the Philadelphia workhouse and the stillbirth her infant were not uncommon in the 18th century and her ultimate survival was certainly in doubt. Sue, however lived through the ordeal and was registered in 1780 in Lancaster County by the Hand Family in accordance with the Pennsylvania Gradual Act of Abolition. She was mentioned again in a letter dated March 9, 1780 from Edward at camp in New Jersey to Kitty in Lancaster.

“Have you got Sue safe at Home? I sent her from Philad with Adam Martin of Millers Town.”

Letter, Historical Society of Pennsylvania

It is not currently known how long Sue remained enslaved in the Hand household but it does not appear that she moved with them to Rock Ford plantation in 1794 since neither the tax records, the slave registry, nor the U.S. Census indicate the presence of an enslaved woman there.

For further reading:

Anderson, A. Prisons and Jails. https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/prisons-and-jails/

R. Tannenbaum Ph.D. (2012) Health and Wellness in Colonial America. http://publisher.abc-clio.com/978031338412

Ad for Sue’s return

Dunlap and Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

21 September 1779, Sat, Page 4

Newspapers.com

High Street Gaol and Workhouse